Tracheal Mites: The Isle of Wight Disease Mystery

In 1906, beekeepers on the Isle of Wight - a small island off the south coast of England - noticed something wrong with their colonies. Bees were crawling on the ground in front of their hives, unable to fly. Their wings were dislocated - held at odd angles, not folded neatly over the abdomen. The colonies weakened and died. The die-off spread from the island to the mainland and across the British Isles. By the early 1920s, an estimated 90 percent of honey bee colonies in Britain and Ireland had been lost.

The cause was unknown. Theories ranged from a new virus to environmental toxins to genetic degeneration. The mysterious epidemic was called "Isle of Wight disease," and it was the Colony Collapse Disorder of its era - a mass die-off with no identified cause, widespread panic, and more theories than evidence.

In 1921, John Rennie, a zoologist at the University of Aberdeen, dissected affected bees and found them: microscopic mites living inside the prothoracic tracheae - the first and largest pair of breathing tubes in the bee's respiratory system. He named the mite Acarapis woodi (the species name honoring his colleague E.A.N. Wood). The Isle of Wight disease had a face, and it was invisible to the naked eye.

The Parasite

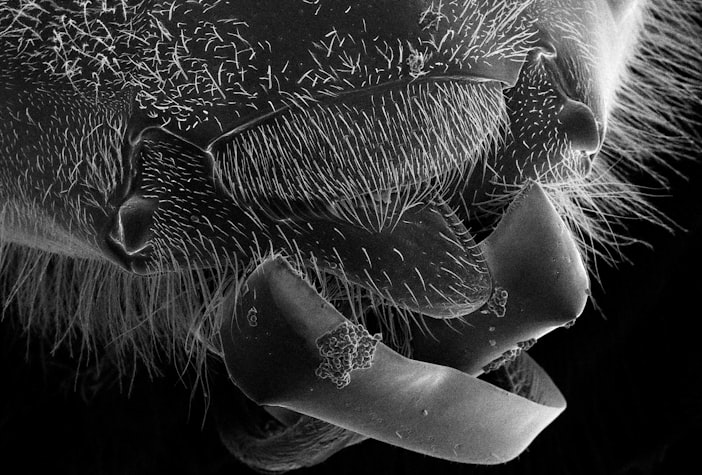

Acarapis woodi is an internal parasite of honey bees - one of the few arthropod parasites that lives inside another arthropod's respiratory system. The adult female mite is approximately 120 to 175 micrometers long - about the width of two human hairs. She's oval, translucent, and equipped with piercing mouthparts that puncture the tracheal wall to feed on hemolymph (bee blood).

The life cycle unfolds entirely inside the bee's tracheal system. A mated female mite enters a young bee's spiracle - one of the external breathing openings on the thorax - typically within the first 4 days of the bee's adult life. Older bees are more resistant to infestation, possibly because the tracheal hairs that guard the spiracle opening become stiffer with age.

Once inside the trachea, the female mite punctures the wall, feeds, and begins laying eggs - approximately 5 to 7 eggs over her lifetime. The eggs hatch inside the trachea. The larval and nymphal stages develop inside the trachea. The juvenile mites feed on hemolymph by piercing the tracheal wall. The entire development from egg to adult takes approximately 11 to 15 days.

When the new generation matures and mates inside the trachea, the young mated females leave the bee through the spiracle, climb onto the bee's external body surface, and transfer to a new young bee through direct physical contact. The transfer typically happens during the close contact of in-hive activities - nurse bees touching, food exchange, grooming.

The Damage

A heavily infested bee - one whose tracheae harbor multiple mites across several generations - suffers from three overlapping problems.

Physical obstruction. The mites, their eggs, their feces, and the hemolymph that leaks from punctured tracheal walls accumulate inside the airway. The trachea, which is normally a clear, elastic tube with a spiral reinforcement (the taenidia), becomes clogged, discolored, and darkened. Severely infested tracheae appear brown or black under a dissecting microscope, compared to the clear or pale amber color of healthy tracheae. The obstruction reduces airflow through the respiratory system.

Hemolymph loss. The feeding punctures drain hemolymph - the insect equivalent of blood, carrying nutrients, hormones, and immune cells. Chronic hemolymph loss weakens the bee's overall physiology, reducing vitellogenin stores, compromising immune function, and shortening lifespan.

Metabolic impairment. The tracheal system delivers oxygen directly to tissues - insects don't use blood to transport oxygen the way mammals do. Oxygen diffuses through the tracheal tubes to the cells. When the tubes are blocked by mites, oxygen delivery to the flight muscles is impaired. The result is the classic symptom: K-wing. The flight muscles can't generate enough power for sustained flight, and the wings dislocate from their normal folded position, sticking out at characteristic angles that beekeepers call "K-wing" because of the shape.

A bee with K-wing can't fly. She crawls. If enough bees in a colony develop tracheal mite infestation - particularly winter bees, whose long lifespan gives the mites more generations to build up - the colony loses its ability to thermoregulate the cluster. Bees with compromised tracheal systems can't generate enough metabolic heat through thoracic shivering. The cluster cools. The colony dies.

This is why tracheal mite kills tend to happen in late winter - the population of mites has been building inside the long-lived winter bees for months, and the cumulative damage reaches a critical threshold when the colony's thermal demands are highest and its ability to replace dead workers is lowest.

The American Arrival

Acarapis woodi was first detected in the United States in 1984, in colonies in Weslaco, Texas. The mite had been in Mexico since at least the 1960s and likely entered the US through migratory beekeeping or natural colony movement across the border.

The US had been the last major beekeeping country without tracheal mites. An import ban on live bees - the Honeybee Act of 1922, the same federal legislation designed to prevent the introduction of bee parasites and diseases - had kept the mite out for 60 years. The ban worked for tracheal mites. It would fail for Varroa, which arrived through a different pathway (or was already present undetected) in the mid-1980s.

The initial tracheal mite impact in the US was severe. Colony losses spiked. Winter mortality increased. Beekeepers in cold northern states - where colonies depend on long-lived, thermogenically competent winter bees - were hit hardest. The losses in the late 1980s and early 1990s were, at the time, described in the same alarmed terms that would later be used for Varroa and CCD. The beekeeping industry was in crisis.

Menthol and Grease

Two treatments emerged as the standard of care for tracheal mites, and both are remarkable for their simplicity.

Menthol. Crystalline menthol, placed on the top bars of the hive in a small bag or container, sublimates (converts from solid to gas) and the menthol vapor fills the hive. The vapor is absorbed through the bees' spiracles and enters the tracheal system, where it kills or repels the mites. Menthol treatment requires ambient temperatures above 60 degrees Fahrenheit (to ensure sublimation) and is typically applied in fall, before the colony forms its winter cluster.

Menthol works. It's a natural compound (derived from mint plants). It's relatively inexpensive. It doesn't contaminate honey if used when supers aren't on the hive. It was approved for use in bee hives by the EPA in 1989.

Grease patties. A mixture of vegetable shortening and granulated sugar, formed into patties and placed on the top bars. The grease coats the bees' bodies as they contact the patty, which disrupts the mite's ability to transfer between bees. The young mated female mites that leave one bee's trachea and walk across the body surface to reach a new bee slip on the greasy surface and can't grip. The transfer is interrupted.

Grease patties don't kill mites already inside the tracheae. They reduce the rate of new infestation by making bee-to-bee transfer difficult. Used throughout the fall and winter, they slow the mite population growth enough to prevent the colony from reaching lethal infestation levels.

Neither treatment eliminates tracheal mites entirely. Both reduce the mite population to manageable levels. The approach is suppression, not eradication.

The Buckfast Resistance

Brother Adam - Karl Kehrle, a Benedictine monk at Buckfast Abbey in Devon, England - spent over 70 years breeding honey bees. His breeding program, which produced the Buckfast bee, was driven largely by the tracheal mite crisis.

Brother Adam had witnessed the Isle of Wight disease devastation firsthand in the early 20th century. He traveled to apiaries across Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East - over 100,000 miles over his lifetime - collecting bee strains and crossbreeding them, selecting for tracheal mite resistance, gentleness, and productivity.

The Buckfast bee demonstrates significant resistance to tracheal mite infestation. The resistance mechanism appears to be behavioral: Buckfast bees groom more actively, removing mites from their bodies before the mites can enter the spiracles. The trait is heritable and has been maintained in Buckfast breeding lines.

In the US, the USDA Baton Rouge lab identified tracheal mite resistance in several bee stocks, including some lines of Russian bees (imported from the Primorsky region, where Apis cerana - and presumably Acarapis woodi or a close relative - has been present for millennia). The Russian bees show reduced mite infestation levels compared to standard Italian or Carniolan stocks, suggesting that coevolution with the mite (or a similar mite) selected for resistance mechanisms.

The Forgotten Mite

Then Varroa destructor arrived, and everything changed.

Varroa was bigger - visible to the naked eye. Varroa was more destructive - killing colonies faster and more reliably. Varroa vectored viruses that created symptoms (deformed wings, paralysis) more dramatic than K-wing. Varroa required new treatments, new management strategies, and a complete restructuring of beekeeping economics. Varroa dominated every conversation, every research grant, every extension service publication.

Tracheal mites didn't disappear. They're still present in US colonies. They still infest and damage bees. But the relative impact of tracheal mites compared to Varroa is like comparing a dripping faucet to a burst pipe. Both are problems. One of them demands all your attention.

The research funding shifted to Varroa. The treatment recommendations shifted to Varroa. The breeding program priorities shifted to Varroa. Tracheal mites became the parasite that beekeepers mention in passing - "oh, and check for tracheal mites too" - after the Varroa discussion takes up the entire meeting.

There's some evidence that tracheal mite prevalence has actually declined in the US since the 1990s, possibly because many of the chemical treatments used for Varroa (Apistan, CheckMite+) had incidental effects on tracheal mites as well. Some researchers suggest that the widespread use of Varroa treatments inadvertently controlled tracheal mites as a side benefit.

Others suggest that bee breeding programs selecting for Varroa resistance may have inadvertently selected for traits (general grooming behavior, hygienic behavior) that also confer some tracheal mite resistance. The selection for one parasite's control may have provided partial control of the other.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing tracheal mite infestation is harder than diagnosing Varroa. You can see Varroa mites with your eyes. Tracheal mites require dissection.

The standard diagnostic method: collect 30 to 50 bees from the hive entrance, kill them by freezing, and dissect the thorax under a dissecting microscope. The prothoracic tracheae are exposed by cutting through the collar (the junction between head and thorax) and pulling back the head to reveal the tracheal trunks. Healthy tracheae are clear or pale amber, with visible taenidial rings. Infested tracheae are darkened - brown to black - and the mites, eggs, and fecal material may be visible inside.

The dissection takes practice. The tracheae are fragile and small. The mites are smaller. A beekeeper who has never done a tracheal mite dissection will need training or a microscope-equipped lab to get reliable results. State apiary inspectors and university extension labs can perform the diagnosis, but the demand for tracheal mite testing has declined as beekeeping attention has focused elsewhere.

The Lesson of the First Mite

The tracheal mite crisis of the early 20th century - the Isle of Wight disease, the 90 percent colony losses, the decades of investigation before the cause was identified - previewed the pattern that would repeat with Varroa a century later. A new parasite arrives. Colonies die en masse. The cause is initially unknown. Theories proliferate. The real culprit is identified through painstaking diagnostic work. Treatments are developed. Resistant stocks are selected. The industry adapts. And then the next parasite arrives, and the cycle begins again.

Acarapis woodi was the first mite crisis. Varroa destructor was the second. The gut parasite Nosema ceranae was arguably the third (replacing Nosema apis and presenting different challenges). The small hive beetle was the fourth. The yellow-legged hornet may be the fifth.

Each new arrival meets an industry that has already spent its reserves - financial, emotional, and biological - fighting the last one. The bees adapt. The beekeepers adapt. The tools improve. And then something else shows up from somewhere else, because the global movement of bees and bee products ensures that every parasite, every pathogen, and every pest eventually reaches every population.

The tracheal mite is still inside the bee. It's still piercing the tracheal wall. It's still draining hemolymph. It's just doing it in the shadow of a bigger crisis, in bees that are already fighting a harder fight, managed by beekeepers who have bigger mites to worry about.

The first mite is always the one you remember. The second mite is the one that changes everything. And the first mite is still there, working quietly inside the breathing tubes, smaller than a hair, older than a memory, and largely forgotten by the industry it once nearly destroyed.