Beeswax: Production, Uses, and Economics

The wax starts out clear.

That's the detail most people miss, and it changes everything about how you understand what's happening inside a hive. When a worker bee secretes a wax flake from the eight mirror glands on the underside of her abdomen, the flake emerges transparent - clear as window glass, about 3 millimeters across and 0.1 millimeters thick. It looks nothing like the golden-yellow substance most people associate with beeswax. The color comes later, after the bee chews the flake, mixes it with enzymes and pollen oils, and works it into comb. The beeswax you know is beeswax that's been processed. The raw material is something stranger: tiny, translucent scales that look like they belong under a microscope.

It takes approximately 1,100 of these flakes to make a single gram of wax.

And the colony pays for every one of them.

The Most Expensive Building Material in Agriculture

Bees produce wax through a metabolic process that is, from an efficiency standpoint, spectacularly wasteful.

Worker bees between 12 and 18 days old do most of the wax production. Their wax glands - specifically the wax-gland-associated fat cells on abdominal segments four through seven - convert sugars from honey into beeswax through a biochemical pathway that consumes staggering quantities of fuel. The commonly cited ratio, confirmed by Whitcomb's 1946 experiments: bees consume approximately eight pounds of honey to produce one pound of wax.

Eight to one. For context, a strong colony might produce 60 pounds of surplus honey in a good year. If that same colony needs to build new comb - which it does constantly, because comb is the infrastructure that makes everything else possible - the wax production alone eats into the honey reserves at a rate that would make any project manager wince.

The hive must also maintain an ambient temperature of 91-97 degrees Fahrenheit for wax secretion to occur. Below that range, the glands don't produce. The colony is simultaneously spending energy to heat the workspace and spending honey to fund the construction materials. It's like building a house where the lumber costs eight times more than the house will sell for, and you also have to keep the construction site at tropical temperatures.

The glands atrophy after the bees transition to foraging duties. Wax production is a young bee's game - a brief window of biological capability that closes as the worker ages out of house duties and into field work. The colony's entire architectural output depends on a rotating workforce of teenagers who will lose the ability to do the job within a week.

300 Compounds That Nobody Can Fake

Beeswax is not a simple substance. It's a blend of more than 300 distinct chemical compounds - hydrocarbons (14%), monoesters (35%), diesters (14%), triesters (3%), hydroxy monoesters (4%), hydroxypolyesters (8%), free acids (12%), acid monoesters (1%), acid polyesters (2%), and roughly 7% of material that researchers haven't fully identified yet. The main constituents are palmitate, palmitoleate, and oleate esters of long-chain aliphatic alcohols with 30 to 32 carbon atoms.

This complexity is exactly why synthetic beeswax exists and exactly why it doesn't work as well.

Lab-engineered blends of esters, fatty acids, and hydrocarbons can approximate beeswax's melting point (62-64 degrees Celsius) and some of its physical properties. Synthetic versions offer consistent quality, controlled melting behavior, and neutral color. What they lack is the full orchestra of 300-plus compounds working in concert - the antibacterial properties, the specific plasticity at hive temperatures, the way natural beeswax breathes and interacts with honey and propolis. Plant-based alternatives like candelilla wax (from the candelilla shrub) and carnauba wax (from the carnauba palm) come closer in some applications but still can't replicate the combination of emollient, protective, and antimicrobial properties that beeswax delivers simultaneously.

Three hundred compounds, produced by an insect, from honey. The recipe has been stable for millions of years. Synthetic chemistry has been trying to match it for decades and keeps falling short.

6,500 Years of Lost Wax

The oldest known use of beeswax in manufacturing dates to approximately 4550-4450 BC - gold artifacts found at Bulgaria's Varna Necropolis, created using the lost-wax casting technique. The process, called cire perdue, works like this: a sculptor forms a detailed model in beeswax, coats it in clay, heats the mold until the wax melts and drains away ("lost"), then pours molten metal into the hollow left behind. The clay is broken away to reveal a metal duplicate of the original wax sculpture.

By 3500 BC, Mesopotamian artisans were using the technique for copper and bronze statues. The ancient Greeks scaled it up for the large bronze sculptures that defined Classical art - the technique that created the kinds of pieces now standing in the Metropolitan Museum was built on beeswax. Roman workshops used it. Renaissance Italian sculptors used it. Fine art foundries still use it today, six and a half millennia after someone in Bulgaria first thought: what if I melted this bee product out of a clay shell and poured bronze in?

Beeswax worked for lost-wax casting because of a specific combination of properties that no other natural material matched: it's pliable enough to carve fine detail, holds its shape at room temperature, melts cleanly at relatively low heat, and leaves no residue in the mold. The 62-64 degree Celsius melting point sits in a sweet spot - hot enough to stay solid during sculpting, cool enough to melt out of a clay mold without requiring temperatures that would crack the mold itself.

The same substance that bees produce to house their brood also housed the bronze that built Classical civilization's art. There's a through-line from a wax gland on a bee's abdomen to the Riace Warriors.

The Apples in Your Grocery Store

Beeswax is designated E901 in the European Union's food additive system and recognized as GRAS (Generally Recognized as Safe) by the US FDA. The applications that most people encounter without realizing it involve fruit and cheese.

The apples, pears, citrus fruits, melons, and pineapples in a typical grocery store produce section are coated with a thin layer of wax - sometimes beeswax, sometimes carnauba, sometimes shellac - that replaces the natural waxy coating removed during washing. The coating prevents moisture loss, extends shelf life, and gives the fruit that suspicious, showroom-quality shine. In the EU, waxed fruit must be labeled as such. In the US, the labeling requirements are less stringent, which means most Americans have been eating trace amounts of beeswax their entire lives without knowing it.

Cheese gets a beeswax coating for the same reason: sealing out air prevents mold growth and extends aging potential. Wax-wrapped cheese wheels are one of the oldest food preservation technologies still in active use.

Humans cannot digest beeswax. Its complex chemical structure of long-chain fatty acids and alcohols passes through the digestive system largely intact, similar to dietary fiber. Which means all the beeswax on all the apples and all the cheese is going straight through, doing exactly nothing nutritionally, serving purely as a packaging material that happens to be produced by an insect.

The Burt's Bees Problem

The cosmetics industry consumes approximately 25% of global beeswax production, and one company dominates the conversation.

Burt's Bees generated 19.3% of all US lip balm and treatment sales in 2026 - over $140 million in revenue from a product category whose foundational ingredient is secreted from the abdomens of honey bees. The brand's entire identity is built on beeswax. The name is in the name. The logo is a bee. The flagship product is a tube of beeswax-based lip balm that retails for under five dollars and has been the bestselling lip balm in the United States for years.

The broader cosmetics market uses beeswax in mascaras, foundations, lotions, creams, and solid perfumes. The material's emollient properties - it softens skin without clogging pores - combined with its ability to help other ingredients bind together makes it functionally irreplaceable in many formulations. Consumer demand for "natural" and "chemical-free" personal care products has accelerated beeswax demand, creating a market dynamic where the same substance beekeepers scrape off their equipment with irritated sighs is commanding premium prices in cosmetics supply chains.

The global beeswax market was valued at approximately $642 million in 2026, with projections reaching over $1 billion by 2034. The growth is driven primarily by cosmetics, pharmaceutical coatings, and the food industry's expanding use of natural glazing agents. A $642 million market built on a substance that each colony produces at a rate of one to two pounds per year.

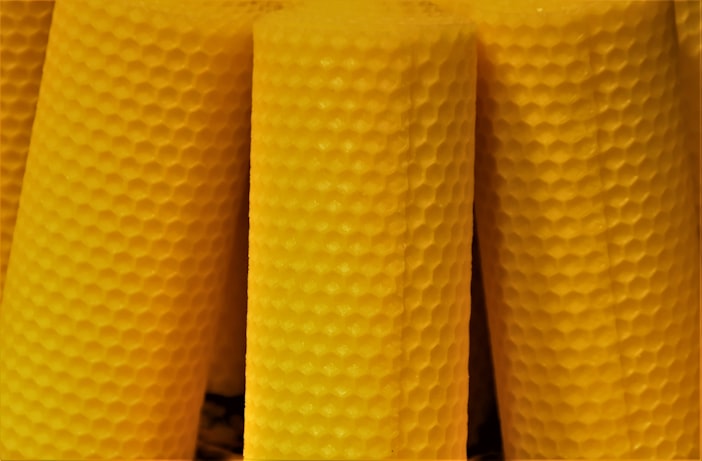

The Church Candle Mandate

Since the 4th century AD, the Roman Catholic Church required that only beeswax candles be used in churches. The theological reasoning was characteristically specific: bees were believed to be blessed by God, making their wax pure and untainted - an appropriate material for illuminating sacred spaces. The practical reasoning was equally sound: beeswax candles burn brighter, longer, and cleaner than tallow (animal fat) candles, produce less soot, and don't bend or droop in warm weather. A tallow candle in a Mediterranean church during August mass would have been a structural failure. A beeswax candle holds its shape.

This single institutional requirement drove European beekeeping economics for over a thousand years. Church, crown, and nobility were the primary patrons of beeswax production. The material was a luxury commodity - ordinary households burned tallow or went dark. The beeswax supply chain was, for most of Western history, a supply chain serving the church.

Candles still account for approximately 40% of global beeswax consumption. The church mandate has relaxed (most modern Catholic churches permit other candle materials), but beeswax candles retain a premium position in the market. A 100% beeswax taper candle costs $3-5, compared to under $1 for a paraffin equivalent. The premium is the complexity: 300 compounds versus petroleum distillate. The candle buyer is paying for chemistry that took millions of years of evolution to develop versus chemistry that took a refinery.

One in Three Is Fake

A 2021 nationwide survey published in PLOS ONE examined beeswax samples from across Belgium and found results that should make anyone buying bulk beeswax pause.

Of 98 beekeeper-sourced samples, 9.2% were adulterated - 2 with paraffin, 7 with stearin (stearic acid). Of 9 commercial beeswax samples, 33.3% were adulterated - all three contaminated samples contained stearin. The paraffin concentrations in adulterated samples ranged from 12% to 78.8%. One "beeswax" sample was nearly four-fifths paraffin.

The adulterants aren't just an economic fraud problem. When adulterated wax makes its way into comb foundation - the pre-stamped wax sheets that beekeepers install in frames for bees to build on - the consequences ripple through colony health. Research has shown that contaminated foundation affects brood development, with paraffin-adulterated comb showing measurably lower brood survival rates. The bees build their nursery on the foundation. If the foundation is 78% petroleum product, the nursery has problems.

Detection requires sophisticated equipment - FTIR-ATR spectroscopy can identify paraffin adulteration at concentrations below 3%, but that's not equipment most beekeepers or small-scale buyers have access to. The researchers recommended using at least two analytical methods for reliable detection, which tells you something about how difficult it is to catch a well-executed adulteration.

The economic incentive is straightforward. Raw beeswax sells for $8-12 per pound at wholesale. Paraffin sells for under $1. The margin on cutting beeswax with paraffin is enormous, and the product looks, at casual inspection, identical. A buyer would need a spectrometer to know they've been cheated. Most buyers don't have spectrometers.

The Scarcity Math

A typical managed colony produces one to two pounds of beeswax per year through normal comb building and replacement. Given the 8:1 honey-to-wax ratio, those one to two pounds represent 8 to 16 pounds of honey the bees consumed just to produce the wax - honey that could otherwise have been harvested as the beekeeper's primary revenue product.

Beekeepers recover wax primarily by melting old, dark comb that's been cycled out of the hive. After several years of use, comb accumulates propolis, cocoon remnants from brood cycles, and contaminants that make it unsuitable for continued use. The old comb gets melted, filtered, and sold - but the yield is modest. Approximately 2.2 pounds of rendered wax per colony per year, on average.

The global beeswax market's $642 million valuation sits on top of this biological constraint. You cannot speed up a wax gland. You cannot make a colony produce more wax without feeding it proportionally more honey. You cannot scale production by adding machinery. Every gram of beeswax on Earth was secreted, one transparent flake at a time, by a bee between 12 and 18 days old, at a metabolic cost of eight pounds of honey per pound of wax.

The retail price spectrum reflects the scarcity and processing levels. Raw, unfiltered beeswax runs $9-10 per pound for individual purchases, dropping to $8 per pound at 100-pound quantities. Cosmetic-grade filtered wax commands $8-30 per pound depending on purity and organic certification. Pharmaceutical-grade, triple-filtered to National Formulary specifications, sits at the premium end.

At every price point, the underlying constraint is the same: 1,100 flakes per gram. Eight pounds of honey per pound of wax. One to two pounds per colony per year. The bees set the production ceiling. The market works underneath it.

The wax starts out clear. The bees chew it yellow. The beekeepers melt it into blocks. The cosmetics companies press it into lip balm. The churches burn it on altars. The foundries lose it in bronze casting molds. And somewhere, in a laboratory in Belgium, a spectrometer reveals that what someone sold as beeswax was mostly paraffin, and nobody noticed until someone thought to check.

The bees keep secreting. The market keeps growing. The 300 compounds keep defying replication. And every gram of it still costs eight pounds of honey - a price the bees have been paying, without negotiation, for longer than humans have been keeping records.